How to teach NLP to non-CS-majors in 2 weeks?

I strongly believe that getting machines to understand natural language, if at all possible, will require much interdisciplinary collaboration. It’s not clear whether NLP models should be biologically plausible or explicitly encode any linguistic structures – but we do know that language is a very complex thing, and no discipline has been able to solve all the problems on its own.

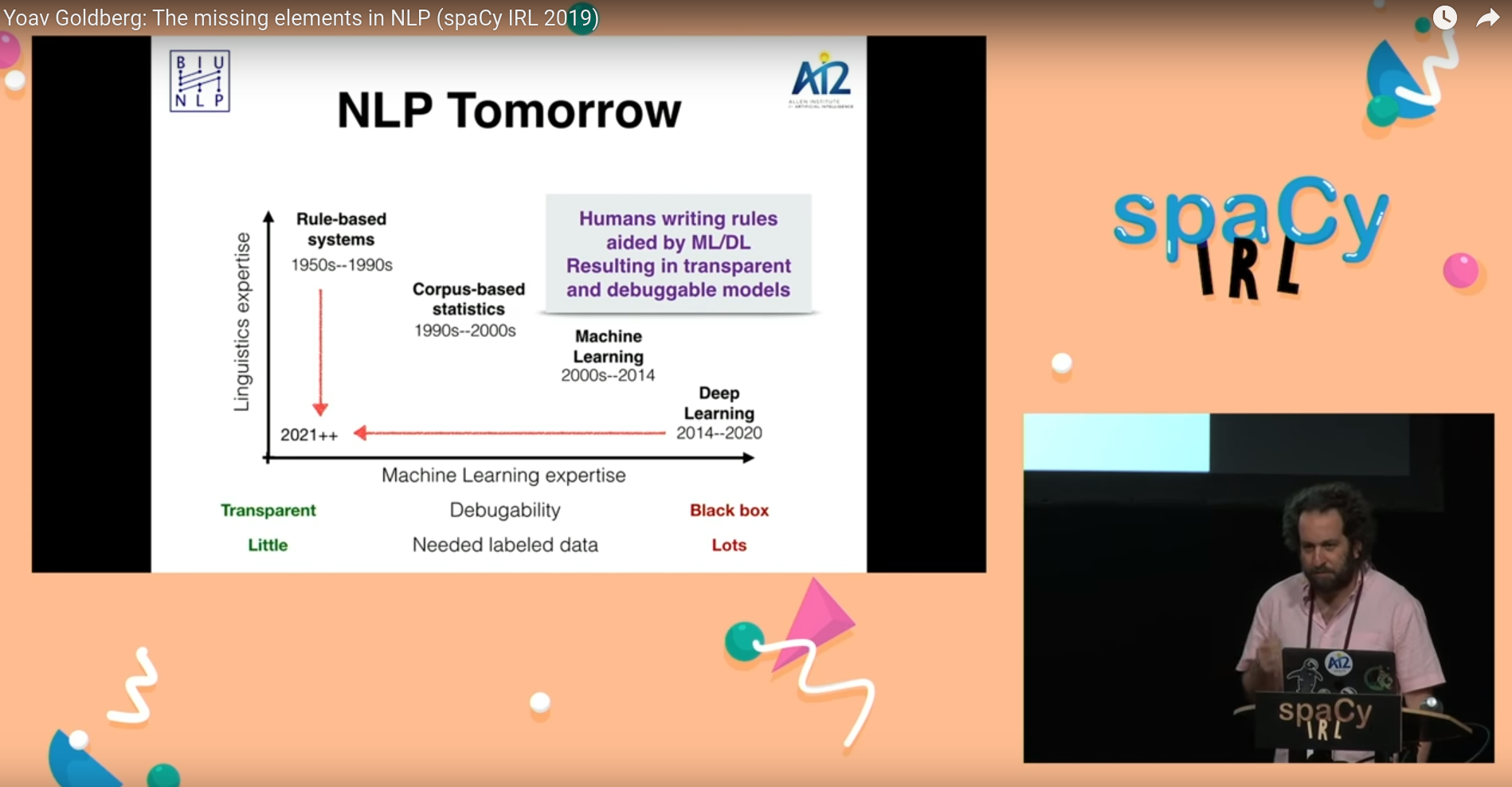

Don’t take just my word for it. Here’s Yoav Goldberg’s slide from his SpacyIRL 2019 talk: the future NLP will require both linguistic and machine learning expertise.

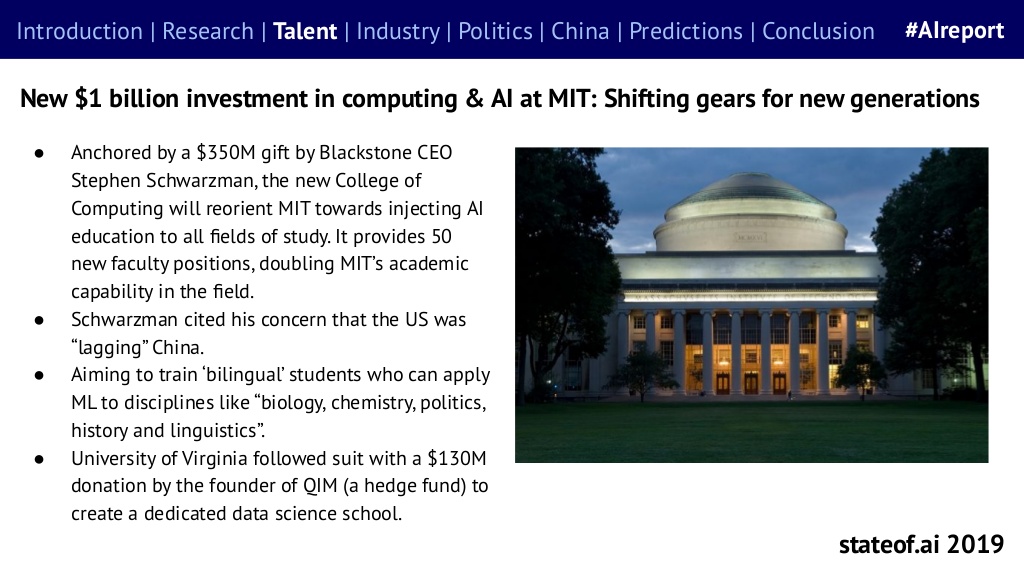

Consider also the raising investment in cross-disciplinary programs in all kinds of data science, aimed to train the new “bilingual” task force. State of AI 2019 reports the following:

So, we need to train this new taskforce. Great idea, right? Let’s just do it.

Why cross-disciplinary programs are hard.Permalink

The problem is, of course, that true interdisciplinarity requires working knowledge of more than one field. This comes at the time when both arXiv and conferences are exploding, and we can barely keep up with the literature even within one narrow sub-field of NLP. Now, imagine that NLP is your second field, and in addition to the arXiv insanity, you also need to keep track of all the latest research on linguistic typology or whatever your original field is.

Moreover, it’s not just about reading more literature. It’s also learning a different mindset, a different way to set and solve problems. In case of NLP for linguistics, it takes time to start seeing everything as “tasks”, and to formulate research hypotheses in a such a way that they could be proved or falsified by ML experiments.

In case of NLP for linguistics, it also involves acquiring a whole lot of technical knowledge that should have come from a large series of undergraduate courses – all in your spare time. Somebody willing to do this must have not only above-average dedication and amount of spare time, but also unusual willingness to look beyond the basic tenets of one’s original discipline. This is objectively hard, and not for everyone.

Case study: Introductory NLP at ESSLLI 2019Permalink

Backgound: I’ve taught in both CS and linguistics university programs before, and I’m told I’m a pretty good lecturer. I have some experience developing curricula, and, most importantly, I’m someone who made the transition from cognitive semantics to a machine learning lab.

With all of that, I came to ESSLLI to teach a 2-week introductory NLP course for theoretical linguists, confident I knew how to do this right.

The original planPermalink

In week 1 my goal was to provide the minimal skill set for getting, processing, and experimenting with textual data with Python, as well as fundamentals of machine learning. In week 2 I aimed to cover the basic neural architectures and the latest issues in evaluation and creation of datasets. I assumed that the students would have only the basic Python skills from an online course (such as this excellent edX course that I started from myself).

Sounds doable, right? I had very positive feedback for my proposal and, as an ex-linguist, I thought I knew what I was getting into.

Of course, the Murphy law did not fail to apply. Here are some things I learned the hard way.

Problem 1: the pool of students is incredibly diverse.Permalink

ESSLLI is a very unique environment where you can meet literally anybody. I was preparing with the linguists in mind, but I found that my class had also physicists, mathematicians, and philosophers (at least 2 of each). Some of the linguists also had much more coding experience than others.

However, this is not only a problem for ESSLLI, and would probably would apply to any elective NLP or data science course. For example, I have just taught a UMass introductory Data Science course aimed at business majors, and I had everybody from chemists to political science.

This means two things for the lecturer:

- at any point you can safely assume that a part of the audience is either bored or confused.

- at any point you can get any kind of question, from something very basic to something you can’t even answer on the spot.

To balance out boredom and confusion, and also to acknowledge the impossibility of humans attending to any one thing for 90 minutes straight, my strategy was to split the class into a short lecture (~30-40 min out of 90) and a hands-on tutorial in Jupyter. I prepared the lectures with the confused part of the audience in mind, and I assumed that the bored part will just dive into Jupyter and keep themselves occupied.

Still, I was definitely not prepared for everything:

Teaching an intro PyTorch tutorial at ESSLLI. Audience is 80% linguists, and I start very confident I know how to talk to former colleagues.

— Anna Rogers (@annargrs) August 13, 2019

A question halfway into the tutorial:

- Sorry, what is "GPU"?

(Sound of my brain overclocking to reassess the rest of the material)

Problem 2: basic Python is not enoughPermalink

I assumed that the students would have taken an online Python course, which in my mind implied familiarity with functions and classes.

What I should have realized is that object-oriented programming is not something that a beginner is going to be able to actually use after just a set of exercises. I know many non-CS researchers who rely on Python heavily for daily experimentation - and manage to do most of it procedurally, in Jupyter notebooks. They might write a few functions to load/save their data that they copy-paste routinely, but they’re not going anywhere near classes. They really don’t need it for what they do.

What this means for an NLP course is that if your deep learning framework relies on relatively complex programming constructs like classes, your students will be stuck with programming before they can even start to get stuck with partial derivatives. I chose vanilla PyTorch, with the goal of showing the students all the building blocks of a simple feed-forward network. My code was heavily commented, and they were able to run it, but I honestly have no idea how much of it could possibly sink in.

I’m still debating with myself whether I should have just gone with fast.ai. If the goal is to just give people tools to run pre-packaged models, then it would definitely be achieved much more efficiently than what I did. But if the goal is, eventually, research, then awareness of all the individual components is certainly to be encouraged.

Problem 3: emerging-curricula messPermalink

At the time that I got my ESSLLI proposal accepted, I did one thing very wrong: I did not try to check what other courses there were, and whether there was potential overlap. The result was that in both weeks of ESSLLI there were two courses with partly overlapping material, that the majority of students taking my classes also attended, and I had to frantically reorganize and add material. In my case, I ended up relying on other people for the overview of fancy neural nets, and using the time for more datasets and methodology discussion, which nobody else was doing.

On the one hand, this is to be expected from a summer school which is a unique, throw-everyone-together event - but I would strongly suspect that an emerging data science program would also have some mess in curricula, because… well… this is all emerging disciplines, and NLP in particular changes so fast that if I were to come to ESSLLI again next year I’d have to replace at least 20% of the material.

The takeaway here is that interdisciplinary programs require also above-average attention to the overall curriculum structure, seeing how your piece fits with everything else that your target students are taking, and NLP in particular requires above-average monitoring of the recent developments. Say, if tomorrow graph neural networks top all leaderboards, we’ll have to somehow teach them.

PyTorch actually helped me to make this point. The students installed version 1.1 in week 1, and by the time we got to week 2 the version 1.2 was already out.

Problem 4: “Introduction to NLP” is actually at least 3 courses.Permalink

This was a big misconception on my part. I really needed to teach 3 different things, all in the space of a single course:

1) The data part: formats, pre-processing, pipeline components, available resources, potential effects, biases and artifacts. By now, this should clearly be a course in itself, and the one where the linguists can immediately make the most difference.

2) The machine learning part: the fundamentals of machine learning experiments, variance/bias, linear and logistic regression, basic neural nets, rnns, attention…

3) The actual NLP, which comes at the intersection of (1) and (2). Discussing the latest cool stuff such as the BERT meltdown is really not feasible without both of them.

If possible, I would perhaps sub-split distributional meaning representations as a course separate from (3), with a gentle primer on linear algebra. That one has to be really gentle, and not longer than 30 minutes at a time. I did make a desperate attempt to run through matrix factorization in half a lecture, as I believe it’s important to think of word2vec&co in context of count-based baselines. I really appreciate the bravery of my students who still showed up on the next day.

Overall, in the course of 10 90-minute lectures and tutorials, I was able to fit maybe 15-30% of each of these courses. If I were to develop a curriculum for the next year’s ESSLLI, I’d try to make sure that there would be a course for (1) and (2) independently, in week 1, so that in week 2 someone would proceed with the actual NLP.

To concludePermalink

So this is what I learned the hard way, and I hope might be helpful for other people working on cross-disciplinary courses. My materials are available on the course website.

I’d like to thank ESSLLI organizers, the great city of Riga (with its fantastic food), and, of course, all of my very brave students.

I’m particularly grateful to the students who came up later and shared their stories. A few of them were in strong computational programs, but many were theoretical linguists, language teachers, translators, students of literature, in departments without a single computational linguist, with no one to ask for advice. These are the people who keep struggling with online coding courses in their spare time, and nobody’s there to tell them that it’s totally normal to spend 5 hours hunting for a silly bug. At least 50% of the class were women, which means 2x impostor syndrome. Rather than getting recognized for their attempt to go across the fence, they feel like they’re wasting time on something they will never be able to do well.

I know this, because that’s exactly how I felt for a really long time, too.