Should the reviewers know who the authors are?

This post is my $0.02 in the ongoing debate about ACL peer review reform. TLDR if you’ve missed that: ACL is discussing the ways to improve peer review, and released short-term and long-term review proposals that generated many lively discussions on Twitter and in ACL 2020. The debate is still going on, and ACL actively solicited community feedback. So far the proposals focused on new workflows and efficiency of the process; I’m arguing for broadening the goals so as to also improve author anonymity – all the way up to the best paper award committees.

Why peer review needs to be fully anonymousPermalink

It is a truth universally acknowledged that when the reviewers aware of the identity of the authors, they are strongly biased towards established authors and famous labs (Tomkins, Zhang, & Heavlin, 2017).

Ok, well, at least it should be a truth universally acknowledged. One of the most famous experiments on this was done nearly 30 years ago (Peters & Ceci, 1982). They resubmitted 12 articles to reputable psychology journals that already published these very same articles - but they changed the authors’ names and institutions changed to unknown names. Only 8% of editors and reviewers noticed the resubmisson, and 89% recommended rejection, in many cases for ‘methodology flaws’!

Note that this was 30 years ago, before we had Twitter and blogs. The research community has since made a lot of progress in developing ‘PR review’ techniques: a famous lab can have a specific preprint widely discussed before it is even submitted for review. That wide discussion by itself creates the impression that the community already accepted and validated this work, and so of course the reviewers should recommend it for acceptance.

That’s not even the worst part. It is a truth less universally acknowledged that non-anonymous peer review, like any other non-anonymous human interaction, is at risk of being compromised by social biases, such as biases by race, gender, ethnicity, age group. There is more than enough evidence to be concerned (Bornmann, Mutz, & Daniel, 2007; Kaatz, Gutierrez, & Carnes, 2014; Hojat, Gonnella, & Caelleigh, 2003), and to do something while we’re educating ourselves on the subject.

A key point here is that this applies even when the biases are unconscious. Say, we may be absolutely sure that neither the race of the authors, nor the prestige of their institution has anything to do with our opinion of a paper. The problem is that our conscious selves are not really trustworthy. So, given human cognitive limitations, the best thing we can do is a fully anonymous peer-review process.

Isn’t it fully anonymous already?Permalink

Wait, isn’t NLP peer review already fully anonymous? Yes and no. *CL conferences officially implement a fully anonymous peer review process, and require the authors to avoid revealing self-citations. However…

ArXiv and anonymity periodPermalink

First, there’s this thing called arXiv. The authors are not prohibited from uploading and publicizing their work a month before submission deadline; this seems to mostly have the effect of shifting the deadline a month earlier. Note that the big labs with more resources and projects are more likely to have at least some of the drafts relatively finished and arXiv-ed before the anonymity period kicks in, and so they are more likely to have at least some papers accepted each year.

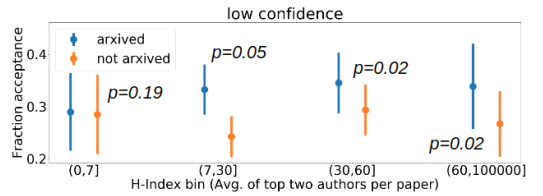

I am not aware of any studies done for *CL conferences (presumably because their peer review data is not available for public analysis) - but ICLR review scores do correlate with arXiv preprint availability (Bharadhwaj, Turpin, Garg, & Anderson, 2020). The effect is particularly noticeable for less confident reviewers who seem to rely more on author reputation (estimated by Google Scholar citation data):

I would speculate that the effect is particularly large for papers by big labs that managed to attract a lot of attention (especially big industry labs with considerable PR resources). Arguably Google AI’s BERT (Devlin, Chang, Lee, & Toutanova, 2019) entirely circumvented the peer review process because the paper was already famous and widely cited by the time it got to NAACL. It is highly unlikely that it could be reviewed anonymously.

Should BERT have gotten the best paper award? Quite possibly, but perhaps we should think through the whole issue of “peer review” vs “PR review”. When something gets so much attention, it just seems highly important, and the reviewers can hardly be expected to be immune to that. If we do accept hype as a valid indicator of scientific merit, we should at least recognize that it is a distinct factor. “PR-reviewed” papers should not compete for conference acceptance and awards with papers that went through peer review anonymously.

Anonymity and acceptance decisionsPermalink

Even if the reviewers have not seen the preprint, they are not the ones who are actually making any acceptance decisions. Area chairs (ACs), senior area chairs (SACs) and program chairs (PCs) may or may not be aware of the identity of the authors; this is up to the conference, and is not announced in capital letters on the conference home page.

Let us note that the ACs and SACs are themselves likely to be senior members of NLP community. As such, they are likely to be well-connected and know much of the work that they evaluate. Even if nobody consciously favors their friends or disfavors any particular social group – the biases are biases precisely because they are unconscious and humans can’t control them very well. Furthermore, speaking for myself, I suspect that when I happen to know the authors and the whole line of work they are pursuing, I may be seeing a bigger pattern than what was clearly spelled out in the paper.

Finally, consider the conference awards. The starting point for those is recommendations by reviewers, who may or may not know who the authors are because of arXiv, but what happens from that point on is equally at the discretion of the conference. COLING 2018 did maintain anonymity even at this stage, but let us take Yoav Goldberg’s word that usually this is not the case.

Arguments against anonymityPermalink

So, at the moment *CL reviewing is at best only partially anonymous. But is this necessarily a bad thing? To be fair, let us hear the counter-arguments.

“Big labs just do better work”Permalink

This is an argument against trying to correct for bias towards big names. The main point is that the quality of the work could be expected to genuinely correlate with the status of a research group. Say, Stanford remains Stanford because it systematically attracts smarter people who are likely to produce superior output. In that case, since peer review is genuinely noisy and difficult, witholding this information from reviewers means witholding a useful signal (Church, 2020).

The counter-argument is that the fame of a big lab may also have a halo effect on a mediocre paper. Everything just looks more trustworthy when it comes from e.g. Harvard - especially in comparison to a paper of similar quality, but by unknown authors. Furthermore, it’s one thing when the fame of a research group rests primarily on its past achievements and reputation, and another when the group itself is new, but gets more favorable treatment simply due to its affiliation and their PR resources.

Kenneth Church argues that the solution to that is “seniority quotas”, where the conference makes a conscious decision to give that much floor to established and up-and-coming labs. My concern here is that we also have the cross-cutting biases for trendy topics, deep-learning-based methodology, SOTA results and many more. These probably can’t be addressed in any other way than by acceptance quotas, while the author fame bias could be handled by fully anonymous review process.

“What difference will it make?”Permalink

The other argument is that it is not clear that fully anonymous review actually improves the quality of the resulting program - but there is plenty of evidence of it failing to weed out bad papers, even in biomedical research where lives literally depend on it (Smith, 2010). So if it doesn’t do what we want it to do, should we even bother? Kenneth Church argues that it is up to the side arguing for anonymity to provide a proof that it increases not only fairness, but also quality:

Obviously, we care about more than just fairness. Experiments supporting double-blind reviewing need to establish that the treatment (double-blind reviewing) is not only more fair than the control (traditional reviewing) but also more effective. Does the treatment accept better papers (with more potential for growth) than the control, or is treatment merely more random than the control? Thus far, most experiments (Tomkins, Zhang, and Heavlin 2017; Stelmakh, Shah, and Singh 2019) have more to say about fairness than effectiveness. (Church, 2020)

I fully agree that the overall goal is to find papers with more scientific merit - but we can’t really measure that reliably, we seem to only agree on which papers are clearly bad (see the NIPS experiment). But theoretically, if we accept that different demographic groups have approximately the same distribution of quality papers, then removing those biases would improve the overall quality of the program. For instance, if male and female first authors have the same ratio of high-quality papers, but the papers by women get systematically under-sampled - that means accepting more papers by men, even when they are in fact inferior.

Can we just use post-publication citation counts as proxy for paper merit, to prove that anonymity does or does not improve the overall program quality? Not really. For a paper to have high impact and “potential for growth”, it needs (a) that there’s room for building on its ideas, (b) that the community would do so. And that second part depends on more than just science. Consider at least the following factors:

- The Matthew effect: the already-eminent scientists get disproportionate credit in cases of collaboration, or when the same discovery is made by independent teams (Merton, 1968);

- Post-publication PR, which is also easier for the big labs that have more resources to write blog posts and travel to give talks. They also receive many more invitations to participate in panels and give talks.

- How papers are received post-publication is still at least partly influenced by the same unconscious biases discussed above. Campaigns like #CiteBlackWomen are a response to an unfortunate reality. And here’s a recent bit of evidence very close to home: preliminary analysis by Yoav Goldberg suggests that the talks by the authors with Chinese-sounding names were viewed less often in the online ACL 2020.

All of that means that even if a great idea from an unknown lab and/or underrepresented community gets published at ACL, it might not make as big a splash as it deserves. That means that fewer people will adopt and build upon its results. Hence the “potential for growth” was never going to be the same.

Granted, we do not know exactly how full anonymity would change our conference programs, but here’s what we do know:

- When ICLR went fully anonymous, we had a natural experiment which showed that preprints do make a difference; so we do know for a fact that the content of the program would change to some extent (Bharadhwaj, Turpin, Garg, & Anderson, 2020).

- The bias against underrepresented communities should be reduced. For instance, there is evidence that when author identity is concealed female first authors get a better chance (Roberts & Verhoef, 2016).

- Even if this does increase randomness in peer review, as Kenneth Church predicts, that might actually be a good thing for progress (Pluchino, Biondo, & Rapisarda, 2018): among other things, their model suggests that it would be more effective to award some research funding randomly, rather than preferentially targeting established researchers.

- a more inclusive process should be beneficial for geographic diversity. In case of NLP, that should propel language inclusivity, which is not great at the moment (Joshi, Santy, Budhiraja, Bali, & Choudhury, 2020). Studying “languages” rather than “English” would certainly be helpful for the goal of modeling “language”. Furthermore, this should improve the flow of ideas and collaborations between subcommunities, and there’s evidence that “ethnically diverse” papers have a larger impact (AlShebli, Rahwan, & Woon, 2018).

Judging by the overall direction of ACL 2020, and the presence of diversity&inclusion chairs in the recent conferences, the ACL organization now does aim to improve diversity, and full anonymity would be helpful for that. I hope that as the social movement towards diversity&inclusion grows, the community would also gradually become more interested in picking up and developing non-mainstream ideas.

“Small labs need arXiv”Permalink

ArXiv preprints are vigorously defended by Dmytro Mishkin and Amy Tabb in the “Hands off ArXiv!”. In particular, they make the following two arguments:

- even without preprints, the big labs will still find it easier to get published than small labs, because they have more resources and more experienced writers. For the small labs arXiv is a lifeline because it enables them to generate some discussion;

- early career researchers need preprints to have something on their CVs when they apply for jobs.

The latter point could actually be solved within an anonymous preprint system: for example, upon submission of a manuscript people could get receipts acknowledging the submission, and those receipts and/or pdfs stamped with submission record information could be provided as part of the application package.

As for the former, it is true that scales are tipped in favor of big labs to begin with. Allen Schmaltz argues that even an anonymous author may be at disadvantage not because the reviewers can guess who they are, but rather who they are not (a member of an established lab with resources and recognizable research agenda). But it is hardly a reason to not to try to reduce systemic biases.

As a case study, one of the inherent disadvantages for most small labs in the world is that the famous big labs tend to be based in the English-speaking countries. Non-native-sounding English nearly got one of EMNLP PC committees to reject all their submissions from Asian and European countries with less than 5 submissions (Church, 2020)! However, this factor is increasingly recognized, and there are initiatives to try to mitigate it. For instance, ACL Student Research Workshop is already running a mentoring program specifically to improve the quality of writing and presentation. ACL 2020 also had sponsorship from Grammarly to help with proof-reading. EMNLP 2020 reviewing guidelines specifically ask the reviewers to focus on the paper substance, not the writing.

The biggest issue, of course, is that early-career researchers do depend vitally on their work being openly available and discussed. I fully agree with that. But it is not impossible to combine that with fully anonymous peer review. Specifically, we need to (a) speed up the review process, (b) develop a culture for discussing anonymous work. I will describe a proposal for how both of these goals could be achieved below.

“ArXiv is all we need”Permalink

I have heard this last argument many times over the discussion of rolling review proposals. Yes, peer review by itself is deeply problematic. Again, it fails to detect serious flaws (Smith, 2010), it is essentially random for papers that are not obviously bad, and it does not necessarily reward great contributions: a recent NLP example is ELMO, that had unenthusiastic reviews at ICLR and then went to take the best paper award at NAACL. So… maybe we don’t need to bother with review at all, anonymous or not? Shall we just embrace preprints and let citation counts be the indicators of the paper quality?

First of all, this is simply not realistic, because academic careers depend on the prestige of publication venues. This is why top-tier conferences also cannot just start accepting more than 25% of papers. Yes, this is arbitrary and has nothing to do with research, but I have not seen any sufficiently detailed alternative proposals. And even if someone came up with one, it would take many years of lobbying universities and research councils to accept it. And it would have to be done by the senior academics who have many other demands on their time.

Second, that is actually not an argument against full anonymity, but against peer review as such. As discussed above, having the crowd “vote” on preprints with citations will suffer from all the same biases: less famous labs and/or authors from marginalized communities are less likely to have their papers noticed organically and/or have the resources to promote them, which will have an impact on the citation count distribution. “PR review” might completely overtake “peer review”. On the other hand, taking full anonymity seriously in peer review and developing a culture of discussing anonymous preprints has a chance of developing a healthier research ecosystem.

ACL rolling review proposal(s)Permalink

So, what can we actually do about all this? Luckily, the arbitrariness of peer review in the recent years and the increasing review load has already led the community to believe that something should be done. ACL already came forward with a long-term review reform proposal. This post is inspired by numerous conversations around this proposal on Twitter and during ACL 2020.

The current version of the rolling review proposal maintains the status quo with respect to anonymity, considering it a separate issue to be addressed later. In this post, I argue that we do need to think of it already to make sure that the new system at least can be more fair than what we have. True, we can’t hope to solve every issue at once, but this one is really big, especially given the raising awareness of societal biases.

In a nutshell, here is the current version of this proposal.

Option 1: review, then acceptPermalink

To decrease the volume of papers that get (re-)reviewed, ACL is proposing to switch to a journal-like rolling review process with two stages:

- Stage 1: papers are submitted to a unified review pool with monthly deadlines, where they undergo fully anonymous peer review. After that is done, the authors have the option to revise-and-resubmit, or they may choose to make their papers public.

- Stage 2: authors of already-reviewed papers may submit their work to conferences/workshops/journals (based on their respective deadlines). The ACs/SACs/PCs make decisions based on the existing reviews, and their own editorial policies. This process may or may not conceal author identity, like it is done today.

Option 2: review+acceptPermalink

The presentation of the rolling review proposal in ACL 2020 was followed by a very lively RocketChat discussion, in which Matt Gardner mentioned an alternative proposal that the review committee also considered, but it didn’t make it past the brain-storming stage. The idea is basically “review+accept”: the journal/conference acceptance decisions would be made inside of the rolling review system, thus maintaining full anonymity.

- Pros: not only full anonymity, but also much faster turnaround!

- Cons: So far the acceptance rates were stable at around 25%, but offline conferences have an extra constraint of the venue space. For instance, if next year we still have room for only 800 papers, but receive over 6000 submissions, we will either have to lower the acceptance rate, or have conferences that are 90% posters, or stick to online conferences. This is a separate issue, but if ACL were to decide to address this by lowering the acceptance rates, it would be harder to do in the review+accept version because the organizers wouldn’t get all the papers at once. Say, a CFP could be announced to run for 4 months, but already in the first month the PCs might accept the maximum number of papers they can for a given physical venue, and stop receiving submissions.

Again, the issue of scaling our conferences is a separate one, and deserves serious consideration. At the moment, it is not clear whether the pros of offline conferences outweigh the environmental and social costs. But if ACL does not opt to cap the total number of accepted papers, “review+accept” would deliver acceptance decisions would arrive a month or two faster than in “review, then accept”. This is significant in the fast-moving world of current NLP.

### Embracing anonymous preprints

In either proposal, the key issue for anonymity is what happens after a paper was reviewed, and before it is submitted for a conference. Suppose the authors aim for ACL, and their paper is submitted for review in August. They have to wait until the ACL CFP is out (or submit to some other venue). Let’s say the paper is reviewed in September and the authors are happy with the reviews.

If they choose to deanonymize, there is the immediate benefit of having a “respectable” peer-reviewed preprint under their names, which is important for those on the job market. But there are two big problems:

- Many papers do not get accepted on the first try. The authors may try a conference and then decide to make changes and go back into the reviewing pool. If they do so, the peer review will no longer be anonymous.

-

The conference acceptance decisions would inherently be partly or fully non-anonymous. As Yoav Goldberg pointed out, in this proposed scheme the situation would actually be worse than it is now, because the editorial role of ACs/SACs/PCs really puts them in the limelight, and their identities will be known to the authors. In other words, the authors will know that it is these specific people that did not want their work in the conference, perhaps despite good reviews. And who wants to make enemies?

btw, it goes both ways: as a SAC/PC in the new system, the authors will know that *you*, *personally* did not find their paper suitable for ACL 2023. this may cause some tricky situations (and all the more incentives for SAC/PC to get papers from influentials/friends in)

— (((ل()(ل() 'yoav)))) (@yoavgo) June 21, 2020

Can we just hide the identities of the editors, so they don’t have to fear retaliation? No, because:

- biases (unconscious or not) would still be at work, even if the editors are senior enough to not worry about making enemies;

- being an area chair or an action editor does go on the CV and is important for academic careers.

But both of these problems can be avoided if we simply embrace the openReview model:

- the papers are made available for all to see as anonymous preprints;

- the anonymous reviews and decisions are also available for all to see;

- there are open comments from the public (and the reviewers would be incentivized to write better reviews if they could not see the open comments until they submitted their opinions);

- the papers would already start collecting citations;

- the system could be set up to provide some kind of receipts for those who need proof of authorship for job applications;

- having a public record of community engaging with papers would be helpful for early career researchers, especially when non-experts evaluate their grant proposals and tenure cases. For that same reason, the system should provide an option to hide non-constructive comments.

Moreover, generally this could be a chance to develop a healthier relationship with preprints in the community: ideally we’d want to look at new work because we want to see the latest results in the area we care about - not because it is something publicized by someone influential. Imagine an openReview-like system equipped with a daily feed of preprints in each subfield. Further imagine that, unlike arXiv, it comes with a dedicated chat/forum, tied to each paper. The RocketChat experience in ACL 2020 made it painfully clear how useful that would be.

arxiv feed

In “review+accept” all papers will have to be discussed either anonymously or post-acceptance, and the rush to see new ideas should help to develop a culture for looking at the work itself. To make things even more interesting, we could disallow the reviewers to see the public discussions until they submitted their own reviews - which would further incentivize them to write better reviews. For the papers that generated good discussions, the authors might choose to keep such discussions public:

I hope I’ve made the case that stage 2 really has to be fully anonymous. But NLP is moving at breakneck speed, and the authors would shoot themselves in the foot to not “publish” their work as soon as it was reviewed. We could offer the option of anonymous preprints, but if it were optional, most people would not go for it because directly publicizing your work would generate much more attention. And then the acceptance decisions would not be made anonymously. And should the paper be rejected and opt to return to the reviewing pool, the second round of reviewing will be inherently compromised.

and that’s something that the community would welcome very much. First, for better or worse, we have this huge class of NLP engineering papers where a big part of claim is the SOTA status of the system. Such papers literally cannot afford to not be accepted at once. It is an open question whether we we might want to consider them a separate paper type that should not compete with “more sciency” papers, but faster turnaround is crucial for other paper types too: longer waits means higher chances of getting scooped, and/or the necessity of update baseline experiments with whatever-became-SOTA-since-submission.

But even if ACL were to go down the road of lowering acceptance rates, I’d argue that the cons of fully anonymous peer review are logistic, and the pros are existential. That makes the game very well worth the candle.

One more plus of “review+accept” is that we have a better chance to establish the culture of discussing anonymous preprints. In both proposals, there will be a pool of papers under review which could be made open to comments from non-reviewers (as long as there’s no COI, and the reviewers do not see those comments until they finish their own). But in “review, then accept” there will be papers that were already deanonymized and then open for discussion: that again has potential for heated discussions around work by big names, which by itself would additionally bias the acceptance decisions. In a way, this is what we have already: it is already possible to post an anonymous preprint, but the chances for anonymous work to get any attention in the flood of preprints propelled by the authors are slim.

ConclusionPermalink

This is my case for fully anonymous reviewing, and for peer review rather than PR review. Since we’re reforming the review system anyway, we have a chance to actually change things - and there is a way to do that which combines full anonymity with the benefits of faster turnaround and a culture of discussing anonymous work.

I’m not in any way involved in the decision-making, nor am I an authority on any of the above issues. However, the ACL review reform committee does solicit community feedback, and might reconsider the review+accept option if there is enough community support.

I hope this post will generate further discussion; to that end, I’ll update the post with a link to a Twitter discussion thread, and I would appreciate any pointers to conversations emerging elsewhere. My goal is to listen, learn, and update this write-up with any necessary clarifications, nuances, further suggestions and counter-counter arguments. Then it’d be great to run some polls to see what the community would prefer. And then ACL will have a clearer case to consider.

This post is based on many conversations with much wiser people, including (alphabetically) Isabelle Augenstein, Emily M. Bender, Jason Eisner, Matt Gardner, Yoav Goldberb, Jacob Anna Korhonen, Graham Neubig, Amanda Stent, and many others. Any misinterpretation is my own. Separate thanks to Emily M. Bender and Matt Gardner for their comments on this post.

[UPDATE 07.2020] The post generated some discussion, people submitted feedback to the ACL reform committee using the official feedback form. No response from the committee so far. Fingers crossed.

[Update 12.2020] While we’re waiting - NEJLT is a new journal for computational linguistics research that implements a fully anonymous review process, all the way up to the editors. Check it out!

ReferencesPermalink

- AlShebli, B. K., Rahwan, T., & Woon, W. L. (2018). The Preeminence of Ethnic Diversity in Scientific Collaboration. Nature Communications, 9(1), 5163. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07634-8

@article{AlShebliRahwanEtAl_2018_preeminence_of_ethnic_diversity_in_scientific_collaboration, title = {The Preeminence of Ethnic Diversity in Scientific Collaboration}, author = {AlShebli, Bedoor K. and Rahwan, Talal and Woon, Wei Lee}, year = {2018}, month = dec, volume = {9}, pages = {5163}, publisher = {{Nature Publishing Group}}, issn = {2041-1723}, doi = {10.1038/s41467-018-07634-8}, url = {https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-07634-8}, urldate = {2020-07-13}, copyright = {2018 The Author(s)}, journal = {Nature Communications}, language = {en}, number = {1} } @article{BharadhwajTurpinEtAl_2020_De-anonymization_of_authors_through_arXiv_submissions_during_double-blind_review, title = {De-Anonymization of Authors through {{arXiv}} Submissions during Double-Blind Review}, author = {Bharadhwaj, Homanga and Turpin, Dylan and Garg, Animesh and Anderson, Ashton}, year = {2020}, month = jun, url = {http://arxiv.org/abs/2007.00177}, urldate = {2020-07-10}, archiveprefix = {arXiv}, eprint = {2007.00177}, eprinttype = {arxiv}, journal = {arXiv:2007.00177 [cs]}, primaryclass = {cs} }- Bornmann, L., Mutz, R., & Daniel, H.-D. (2007). Gender Differences in Grant Peer Review: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 1(3), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2007.03.001

@article{BornmannMutzEtAl_2007_Gender_differences_in_grant_peer_review_meta-analysis, title = {Gender Differences in Grant Peer Review: {{A}} Meta-Analysis}, shorttitle = {Gender Differences in Grant Peer Review}, author = {Bornmann, Lutz and Mutz, R{\"u}diger and Daniel, Hans-Dieter}, year = {2007}, month = jul, volume = {1}, pages = {226--238}, issn = {1751-1577}, doi = {10.1016/j.joi.2007.03.001}, url = {http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1751157707000363}, urldate = {2020-07-13}, journal = {Journal of Informetrics}, language = {en}, number = {3}, series = {The {{Hirsch Index}}} } - Church, K. W. (2020). Emerging Trends: Reviewing the Reviewers (Again). Natural Language Engineering, 26(2), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324920000030

@article{Church_2020_Emerging_trends_Reviewing_reviewers_again, title = {Emerging Trends: {{Reviewing}} the Reviewers (Again)}, shorttitle = {Emerging Trends}, author = {Church, Kenneth Ward}, year = {2020}, month = mar, volume = {26}, pages = {245--257}, publisher = {{Cambridge University Press}}, issn = {1351-3249, 1469-8110}, doi = {10.1017/S1351324920000030}, url = {https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/natural-language-engineering/article/emerging-trends-reviewing-the-reviewers-again/10CDC1D71E1AEB21456CFBDA187CBCB6}, urldate = {2020-05-12}, journal = {Natural Language Engineering}, language = {en}, number = {2} } - Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 4171–4186.

@inproceedings{DevlinChangEtAl_2019_BERT_Pre-training_of_Deep_Bidirectional_Transformers_for_Language_Understanding, title = {{{BERT}}: {{Pre}}-Training of {{Deep Bidirectional Transformers}} for {{Language Understanding}}}, shorttitle = {{{BERT}}}, language = {en-us}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the 2019 {{Conference}} of the {{North American Chapter}} of the {{Association}} for {{Computational Linguistics}}: {{Human Language Technologies}}, {{Volume}} 1 ({{Long}} and {{Short Papers}})}, url = {https://aclweb.org/anthology/papers/N/N19/N19-1423/}, author = {Devlin, Jacob and Chang, Ming-Wei and Lee, Kenton and Toutanova, Kristina}, month = jun, year = {2019}, pages = {4171-4186} } - Hojat, M., Gonnella, J. S., & Caelleigh, A. S. (2003). Impartial Judgment by the “Gatekeepers” of Science: Fallibility and Accountability in the Peer Review Process. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 8(1), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022670432373

@article{HojatGonnellaEtAl_2003_Impartial_Judgment_by_Gatekeepers_of_Science_Fallibility_and_Accountability_in_Peer_Review_Process, title = {Impartial {{Judgment}} by the ``{{Gatekeepers}}'' of {{Science}}: {{Fallibility}} and {{Accountability}} in the {{Peer Review Process}}}, shorttitle = {Impartial {{Judgment}} by the ``{{Gatekeepers}}'' of {{Science}}}, author = {Hojat, Mohammadreza and Gonnella, Joseph S. and Caelleigh, Addeane S.}, year = {2003}, month = mar, volume = {8}, pages = {75--96}, issn = {1573-1677}, doi = {10.1023/A:1022670432373}, url = {https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022670432373}, urldate = {2020-07-13}, journal = {Advances in Health Sciences Education}, language = {en}, number = {1} } - Joshi, P., Santy, S., Budhiraja, A., Bali, K., & Choudhury, M. (2020). The State and Fate of Linguistic Diversity and Inclusion in the NLP World. ArXiv:2004.09095 [Cs].

@article{JoshiSantyEtAl_2020_State_and_Fate_of_Linguistic_Diversity_and_Inclusion_in_NLP_World, title = {The {{State}} and {{Fate}} of {{Linguistic Diversity}} and {{Inclusion}} in the {{NLP World}}}, author = {Joshi, Pratik and Santy, Sebastin and Budhiraja, Amar and Bali, Kalika and Choudhury, Monojit}, year = {2020}, month = jun, url = {http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.09095}, urldate = {2020-06-04}, archiveprefix = {arXiv}, eprint = {2004.09095}, eprinttype = {arxiv}, journal = {arXiv:2004.09095 [cs]}, primaryclass = {cs} } - Kaatz, A., Gutierrez, B., & Carnes, M. (2014). Threats to Objectivity in Peer Review: The Case of Gender. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 35(8), 371–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2014.06.005

@article{KaatzGutierrezEtAl_2014_Threats_to_objectivity_in_peer_review_case_of_gender, title = {Threats to Objectivity in Peer Review: The Case of Gender}, shorttitle = {Threats to Objectivity in Peer Review}, author = {Kaatz, Anna and Gutierrez, Belinda and Carnes, Molly}, year = {2014}, month = aug, volume = {35}, pages = {371--373}, publisher = elsevier, issn = {0165-6147}, doi = {10.1016/j.tips.2014.06.005}, url = {https://www.cell.com/trends/pharmacological-sciences/abstract/S0165-6147(14)00108-4}, urldate = {2020-07-13}, journal = {Trends in Pharmacological Sciences}, language = {English}, number = {8}, pmid = {25086743} } - Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew Effect in Science: The Reward and Communication Systems of Science Are Considered. Science, 159(3810), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.159.3810.56

@article{Merton_1968_Matthew_Effect_in_Science_reward_and_communication_systems_of_science_are_considered, title = {The {{Matthew Effect}} in {{Science}}: {{The}} Reward and Communication Systems of Science Are Considered}, shorttitle = {The {{Matthew Effect}} in {{Science}}}, author = {Merton, Robert K.}, year = {1968}, month = jan, volume = {159}, pages = {56--63}, publisher = {{American Association for the Advancement of Science}}, issn = {0036-8075, 1095-9203}, doi = {10.1126/science.159.3810.56}, url = {https://science.sciencemag.org/content/159/3810/56}, urldate = {2020-07-13}, chapter = {Articles}, copyright = {\textcopyright{} 1968}, journal = science, language = {en}, number = {3810}, pmid = {5634379} } - Peters, D. P., & Ceci, S. J. (1982). The Fate of Published Articles, Submitted Again. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(2), 199–199. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00011213

@article{PetersCeci_1982_fate_of_published_articles_submitted_again, title = {The Fate of Published Articles, Submitted Again}, author = {Peters, Douglas P. and Ceci, Stephen J.}, year = {1982}, month = jun, volume = {5}, pages = {199--199}, publisher = {{Cambridge University Press}}, issn = {1469-1825, 0140-525X}, doi = {10.1017/S0140525X00011213}, url = {https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/behavioral-and-brain-sciences/article/fate-of-published-articles-submitted-again/17914E617A57CDF8ABF3D95F9F28E7FE}, urldate = {2020-05-20}, journal = {Behavioral and Brain Sciences}, language = {en}, number = {2} } - Pluchino, A., Biondo, A. E., & Rapisarda, A. (2018). Talent versus Luck: The Role of Randomness in Success and Failure. Advances in Complex Systems, 21(03n04), 1850014. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219525918500145

@article{PluchinoBiondoEtAl_2018_Talent_versus_luck_role_of_randomness_in_success_and_failure, title = {Talent versus Luck: The Role of Randomness in Success and Failure}, shorttitle = {Talent versus Luck}, author = {Pluchino, Alessandro and Biondo, Alessio Emanuele and Rapisarda, Andrea}, year = {2018}, month = may, volume = {21}, pages = {1850014}, issn = {0219-5259}, doi = {10.1142/S0219525918500145}, url = {https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/10.1142/S0219525918500145}, urldate = {2019-10-28}, journal = {Advances in Complex Systems}, number = {03n04} } - Roberts, S. G., & Verhoef, T. (2016). Double-Blind Reviewing at EvoLang 11 Reveals Gender Bias. Journal of Language Evolution, 1(2), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/jole/lzw009

@article{RobertsVerhoef_2016_Double-blind_reviewing_at_EvoLang_11_reveals_gender_bias, title = {Double-Blind Reviewing at {{EvoLang}} 11 Reveals Gender Bias}, author = {Roberts, Se{\'a}n G. and Verhoef, Tessa}, year = {2016}, month = jul, volume = {1}, pages = {163--167}, publisher = {{Oxford Academic}}, issn = {2058-4571}, doi = {10.1093/jole/lzw009}, url = {https://academic.oup.com/jole/article/1/2/163/2281905}, urldate = {2020-07-10}, journal = {Journal of Language Evolution}, language = {en}, number = {2} } - Smith, R. (2010). Classical Peer Review: An Empty Gun. Breast Cancer Research, 12(4), S13. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2742

@article{Smith_2010_Classical_peer_review_empty_gun, title = {Classical Peer Review: An Empty Gun}, shorttitle = {Classical Peer Review}, author = {Smith, Richard}, year = {2010}, month = dec, volume = {12}, pages = {S13}, issn = {1465-542X}, doi = {10.1186/bcr2742}, url = {https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2742}, urldate = {2020-05-17}, journal = {Breast Cancer Research}, number = {4} } - Tomkins, A., Zhang, M., & Heavlin, W. D. (2017). Reviewer Bias in Single- versus Double-Blind Peer Review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(48), 12708–12713. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707323114

@article{TomkinsZhangEtAl_2017_Reviewer_bias_in_single-_versus_double-blind_peer_review, title = {Reviewer Bias in Single- versus Double-Blind Peer Review}, author = {Tomkins, Andrew and Zhang, Min and Heavlin, William D.}, year = {2017}, month = nov, volume = {114}, pages = {12708--12713}, issn = {0027-8424, 1091-6490}, doi = {10.1073/pnas.1707323114}, url = {http://www.pnas.org/lookup/doi/10.1073/pnas.1707323114}, urldate = {2020-07-13}, journal = {Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences}, language = {en}, number = {48} }