AI ‘News’ Content Farms Are Easy to Make and Hard to Detect

How bad is the synthetic news problem?

Do you feel like most sources of information that you used to rely on, have gotten worse? You’re right: Internet is already flooded with AI-generated content. I’m a NLP researcher, so I’m mostly monitoring the cases involving text, but here are just a few examples within that domain:

- Amazon is filled with scammy AI-generated summaries of real books as well as garbage ‘books’ with advice in high-risk areas, e.g. on mushroom foraging . As a mitigation policy, they currently limit the number of self-published book that an author can upload in a day to three (yes, you read that right!)

- fake consumer reviews and social media posts

- changing policies on community-moderated websites: e.g. both Quora and StackOverflow, which initially prided themselves on authentic content and moderation, are now welcoming AI-generated ‘content’

- SEO heists: websites explicitly generated to resemble a known high-quality competitor website, and drive the internet traffic away from it

- old high-reputation sites resurrected as AI zombies

- ‘obituary pirate’ industry: fake reports of someone’s death (real or not), to capitalize on spike in search phrases from people trying to figure out what actually happened

To be clear, the above problems are not new: review farms, SEO ‘content’ etc have existed before LLMs went mainstream. E.g. here’s a 2017 discussion of the problem with fake reviews on customer review websites like Yelp. But the scale of the problem has changed, as generating such ‘content’ today now does not even require technical knowledge.

This year I contributed to a study published at ACL 2024, led by Giovanni Puccetti from CNR Pisa. This study focused on the specific problem of synthetic ‘news’: websites generated to resemble legitimate news outlets, but entirely filled with synthetic text without any clear traces of human editors involved. Here is a screenshot of such a website:

This particular example appears to be aimed simply at serving ads, to people who visit because they think it’s a legitimate information source. Here the model that was used to generate the content is clearly bad enough that the synthetic nature of the text is obvious - and still this site must have been making its owners enough money, since it’s been up for at least a year. The main harms are waste of user time and resources, and potentially also misinformation (if the reader does not realize that this source is scammy, and comes away misinformed). There are also websites that paraphrase & republish content of real news sites. The main victim in this case is to the original outlet, from which the content is stolen, and the reader may also come away with mis/disinformation. Finally, synthetic ‘news’ may disseminate propaganda narratives, potentially harming not just the individual reader, but the society overall. The disinformation campaigns are trying to mix such narratives with real stories, so that they are perceived as more credible.

At present, the only organization I’m aware of that tries to estimate the prevalence of such ‘news’ is NewsGuard, a for-profit organization that also provides ‘reputation management’ services. Newsguard provides as a service their ratings of various news outlets, including their list of unreliable websites manually identified by their team. In April 2023 they reported 49 such websites. In August 2024, the latest count is 1,021. At present this is the only tracker I’m aware of, and Newsguard list is not public (it is a for-profit company that sells access to that list through a browser extension). So it is hard to tell how accurate this is as an estimate of the size of the problem, but the examples I could find check out. Their criteria for identifying such sites are quite narrow (e.g. AI-generated website with minimal human editing would not count), and so there probably are a lot more spammy sites that are just masking it better.

Importantly, the issue already went far beyond English. At present, Newsguard reports that they identified such websites in 16 languages: Arabic, Chinese, Czech, Dutch, English, French, German, Indonesian, Italian, Korean, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Thai, Turkish. A separate, though related, issue is the use of audio/image/video deep fakes to provide seeming legitimacy to fake stories: e.g. in a recent Slovakia elections fake audio recordings went viral two days before elections, damaging the progressive candidate who then lost to a populist with a pro-Russian policy on Ukraine (Meaker, n.d.)).

At present, there is little recourse. Even when spammy sites are identified and called out as such, this does not automatically damage their standing in search engine results, which is what they’re after. Voice of America attempted to reach out to owners of several such websites, but received either no or uninformative responses (Guess, 2024). They conclude that ‘part of the problem in accountability is the difficulty in tracing the owners or producers of the sites’.

According to Newsguard, 90% of ads supporting these websites are through the Google ad services. In response to request from Voice of America (Guess, 2024), Google said that they could not verify that since Newsguard does not share their list of sites (which of course it would not share, since it is their main business asset). But if their list can be considered as an independent test for whatever strategies Google itself is employing to detect spammy websites - these strategies do not appear to work well at present.

Plausible synthetic ‘news’ is (too) easy to generate, even beyond English

For our study, we used a relatively old LLM - the first generation Llama (7B and 65B parameters) (Touvron et al., 2023). It is a ‘mostly-English’ model: we know it was not trained to be multilingual, but its training data included Italian Wikipedia (about 500K articles). It could have also seen some other Italian web texts, but there were deliberate efforts to exclude non-English sources. We further used 40K Italian news articles from an open dataset CHANGE-it (Mattei, Cafagna, Dell’Orletta, Nissim, & Gatt, 2020). We fed the model the first thirty tokens of real news articles as a prompt, and generated its continuation. Then we recruited 93 native speakers of Italian to determine whether the text is synthetic or not. They were shown either the original news articles, or their versions with synthetic endings. For the best model (fine-tuned 65B Llama), the accuracy of our native speakers was only 64% (vs 50% random chance).

This result is in line with the experiments OpenAI did to show that already GPT-3 could generate news articles in English that could not be easily detected by humans (Brown et al., 2020). The new aspect of our work is showing that the problem goes beyond English. We are not claiming that any language + model combination would be equally successful, but the later models (especially multilingual ones) could be expected to do even better than the old Llama we used.

We note that creating a model that could power a scammy news-like website now comes with very few technical or financial difficulties, which could be expected increase the number of bad actors – and would be in line with the proliferation of such websites discussed above. Renting GPUs on cloud providers such as Amazon is now relatively cheap, and it would require as little as 100$ to replicate one of our LLM training sessions and data generation. The technical barrier to fine-tuning LLMs is also low now, thanks to tools like Huggingface’s Autotrain. We do not criticize open-sourcing such tools, but we hope that our results would highlight the problem with detecting synthetic text, and necessity of more research on synthetic text detection.

Synthetic ‘news’ is currently nearly-impossible to detect ‘in the wild’

Supervised detection.

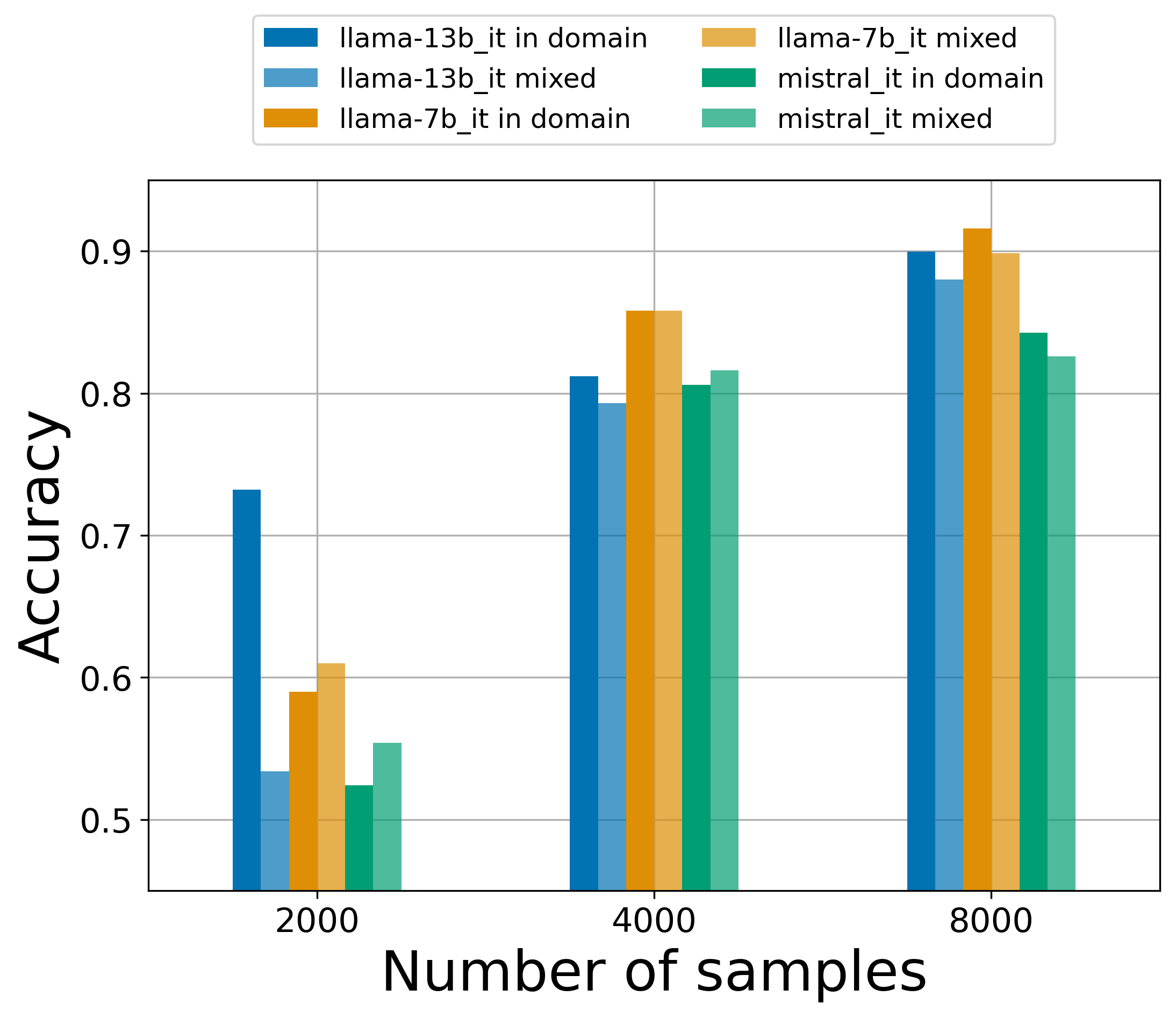

Methodology. The core idea behind this approach is to train a binary classifier on a collection of human-written and synthetic texts. The core problem is that one needs to collect such a dataset, ideally balanced, and that this dataset should represent the distribution of all possible human- and machine-written texts. This seems conceptually non-feasible, even within a given domain such as news. We experimented with training datasets of various sizes (2K, 4K and 8K) and with various distributions of human-written texts:

- in-domain: all human samples come from one dataset (CHANGE-it (Mattei, Cafagna, Dell’Orletta, Nissim, & Gatt, 2020))

- mixed: 50% human samples come from CHANGE-it, and 50% from DICE, a different Italian news dataset (Bonisoli, di Buono, Po, & Rollo, 2023) This allows us to see whether the task becomes more difficult for classifier when it has to represent a more complex distribution of human-authored texts. We also experimented with 3 models used for the machine-generated text: llama2-7b, llama2-13b, and mistral-7b. The classifier was based on xlm-roberta-large.

What we found: for all generator models, the classifier trained on mixed distribution gets consistently worse performance than in-domain (and our mix of just two datasets is a lot simpler than the real distribution of human-authored news). Also, at least 4K samples are needed to get accuracy in the range of 80%.

Verdict: not a practical solution. In reality, the distribution of all possible human-authored texts (even just for Italian news) is much more complex than our settings with 1-2 datasets for Italian. Perhaps this could be the core reason for why OpenAI pulled its own classifier ‘due to low accuracy’. And also we need to collect at least 4K samples of texts. That takes time and effort, and ideally we would like to take action on the scammers before they publish that much.

Approaches based on token likelihoods

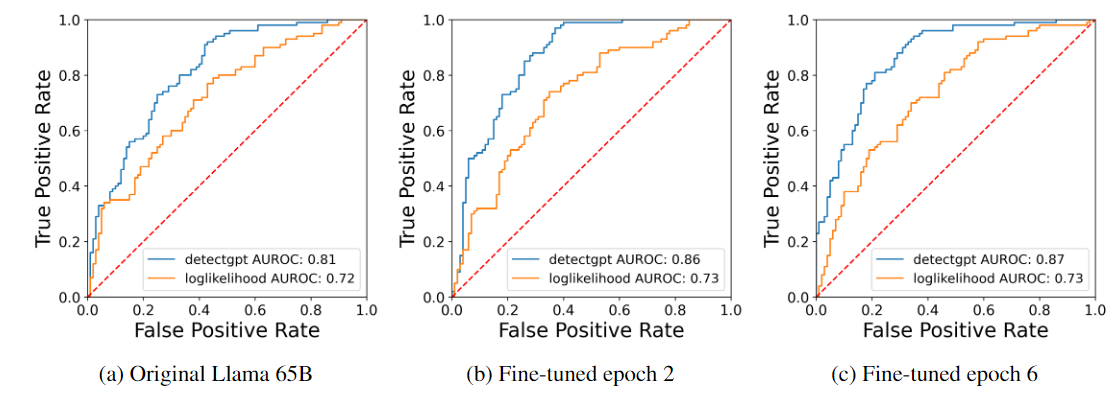

Methodology. The methods based on token likelihoods assume that we have access to the token likelihood information from the model. We experimented with log-likelihood and DetectGPT (Mitchell, Lee, Khazatsky, Manning, & Finn, 2023) approaches (DetectGPT normalizes the log-likelihood score based on sentence modifications generated by another model, IT5-large (Sarti & Nissim, 2022) in our case). The task is to determine whether a given text came from our llama1, either original version or after fine-tuning on CHANGE-IT news dataset.

What we found. The simple log-likelihood does not seem to react to fine-tuning at all: the ROC curve is about the same for pre-trained and fine-tuned models. Detect-GPT has a consistently higher ROC curve than log-likelihood, and does rise 5-6 points for fine-tuning. This is counter-intuitive, because fine-tuning should have made the task more rather than less difficult: by qualitative analysis we found that without Italian fine-tuning the original llama tends to switch to English in the middle of the text, which is highly unnatural and was noticed by our human raters.

We also experimented with using token likelihood information from other models to detect an unknown model. The good news is that even a little fine-tuning data, similar to data that the scammers could have used, is enough. The bad news is that this only seems to work well when the models used for detection and generation are the same. See the paper for details.

Verdict: not a practical solution. If we are trying to detect whether a given suspicious text was written by a model, we do not have access to the token likelihoods in the first place. And there are already too many ‘open’ models to check them all – not to mention the commercial models provided via API without access to token likelihodd information, or custom non-public models.

What about watermarking?

Watermarking assumes that the scammers used a model that comes with a watermark. If the watermark is applied at generation time to an ‘open’ model, such as red-green watermarking (Kirchenbauer et al., 2023), it is safe to assume that they would try to remove it. If it is embedded in model weights, it is also relatively simple to remove it by fine-tuning (which they would likely do anyway). If the scammers used a commercially available model, tampering at the source could be ruled out, but the many current commercially available models do not appear to be watermarked (Gloaguen, Jovanović, Staab, & Vechev, 2024). And finally, even if the text was originally watermarked, the watermark could be weakened and even removed by further manipulating the text by a non-watermarked model, e.g. paraphrasing or human editing (Kirchenbauer et al., 2023).

Moreover, even if we assume that the watermark is intact (i.e. if the scammers were too lazy to remove it), we have the same problem as with approaches based on token likelihoods: simply too many models to test. For watermarking solutions to be practical, there would have to be a centralized repository of all known watermarks, where one could submit a text sample to check against them all in one step. At present, there do not seem to be any efforts in that direction.

Conclusion

Where do we go from here? The methods relying on token probability distributions currently seem to be the best bet for synthetic text detection methods - but even among the open source models there are already too many options to check, given a suspicious text sample.

This does not entail that open source models should be banned, but we do need to consider ways forward that encourage their development that is responsible by design. Ideally watermarking would be built into model weights, so that it would be at least difficult to remove, and there would ideally be a centralized service enabling anybody to check whether a given text contains any of the known watermarks. For ‘closed’ models watermarking should be even easier, since they control the generation process and ensure that the watermark is applied.

Should we bother at all though, if none of the strategies is likely to be fully successful? Any watermark can probably be removed, if you try hard enough, and the most villainous agents (e.g. content farms acting on behalf of hostile governments) are likely to be sufficiently well-funded to develop their own models if they need to. That is all true, but I will borrow an analogy from Prof. Hany Farid (UCB): we do lock our doors, although we know that there are people who can unlock most common household locks. But since we know that it is a relatively rare skill, it is still rational to use household locks as defense. Similarly, measures that significantly raise the barrier for scammers should at least lower the volume of scammy websites.

Assuming that the research community does mananage to develop better measures for identifying spammy websites - there should be a clear, transparent, and public-accessible way to trigger action on scammy websites. Their owners are now hard to track, and the sites are hard to take down, and it is hard to change any of that without changing Internet in a way that would also endanger people who need the protection of anonymity (e.g. activists in authoritarian regime countries). But at least for the scammy websites that only try to serve ads by misrepresenting their content as human-authored - perhaps there should be a process to at least report them and cut off their monetization. This is their raison d’être.