Peer review in NLP: resource papers

Dangerous preconceptions about resource papers

Most success stories in NLP are about supervised or semi-supervised learning. Fundamentally, that means that our parsers, sentiment classifiers, QA systems and everything else are only as good as the training data, and that fact makes data and model engineering equally important for further progress. This is why top-tier conferences of Association for Computational Linguistics usually have a dedicated “Resources and evaluation” track, and awards for best resource papers.

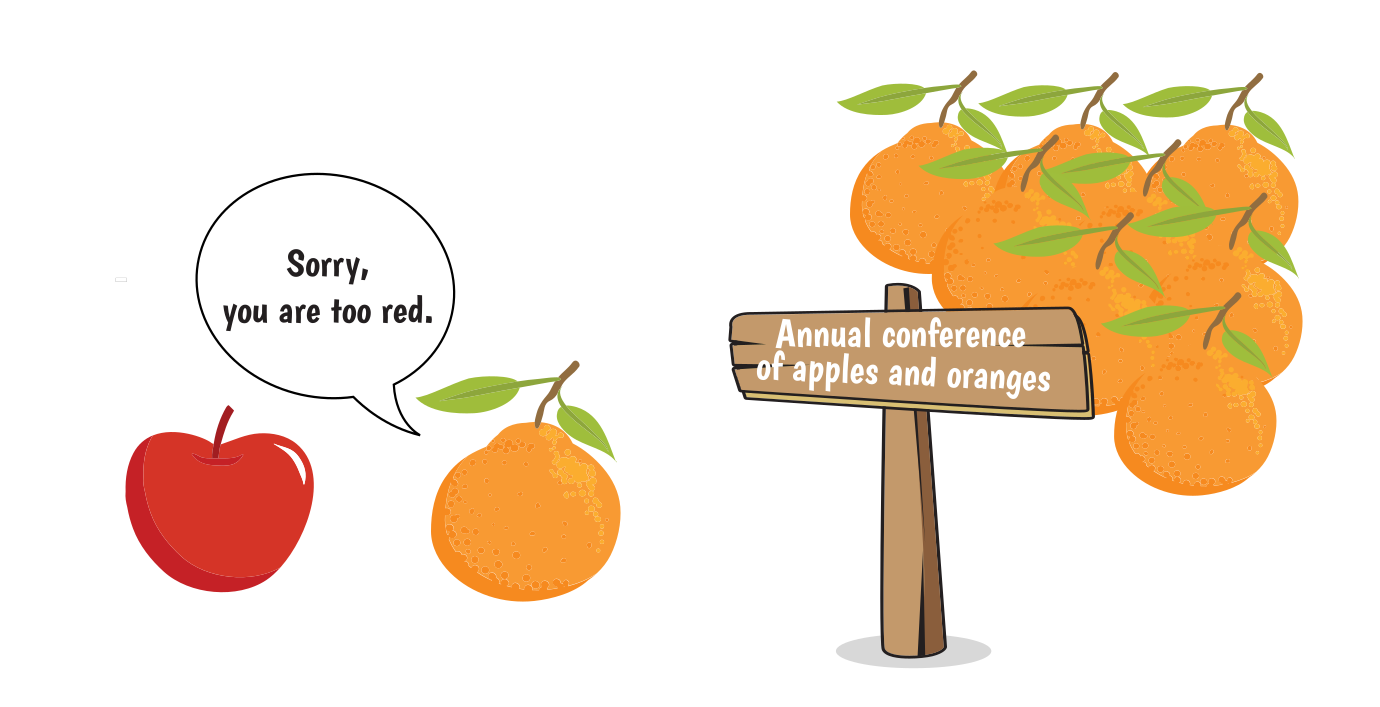

However, creating models and resources are tasks that require different skill sets, traditionally come from different fields, and are often performed by people who have different expectations of what a paper should look like. That turns reviewer assignment into a minefield: an apple looks wrong if you expect an orange. With the best intentions on all sides, a paper may be rejected not for any actual flaws, but for its fundamental methodology.

This post grew out of online and offline discussions with many frustrated authors. One thing is clear: a submission is a waste of both the authors’ and the reviewers’ time, if they fundamentally disagree about what a paper should even look like. I hope it would help the people who use data to better understand the people who make data, and to provide better reviews for their papers.

Let us start by dispelling some myths about resource papers. Unfortunately, all the quotes below come from real *ACL reviews!

Myth 1: Resource papers are not science

Perhaps the clearest example of this view is cited by Rachel Bawden. An ACL 2019 reviewer gave the following opinion of her MT-mediated bilingual dialogue resource (Bawden, Rosset, Lavergne, & Bilinski, 2019):

The paper is mostly a description of the corpus and its collection and contains little scientific contribution.

Given that ACL 2019 had a dedicated “Resource and evaluation” area, it seems impossible that this kind of argument should even be made, much less considered acceptable in a review! To be clear, construction of resources does add knowledge in at least 3 ways:

- they are prerequisite to any knowledge obtainable from modeling;

- in addition to the resource, there may be annotation guidelines or new data collection methodology;

- iterative guidelines development based on annotation increases the knowledge of long-tail phenomena.

Myth 2: Resource papers are more appropriate for LREC or workshops

Most *ACL conferences offer a dedicated “Resource and evaluation” track, yet the authors of resource papers are often advised to take their work to LREC or some thematic workshop instead. Again, let us borrow a quote from Rachel Bawden’s ACL 2019 review:

This paper is not suitable for ACL in my opinion.. It is very suitable for LREC and for MT specific conferences and workshops.

This view is perhaps related to the widespread perception that NLP system engineering work is somehow more prestigious than work on resources. Since *ACL conferences are top-tier, resource papers should almost by definition go to workshops and the lower-ranking LREC conference.

This view is both unfair and counter-productive. First, the authors of NLP engineering papers typically get several chances to submit to main conferences during a year. LREC is the only conference specializing in resources, and it’s bi-annual.

Second, the progress in NLP depends on the co-evolution of systems and benchmarks. NLP benchmarks are not perfect, and when we get stuck on any of them for too long we are likely to start optimizing for the wrong thing, publishing a lot of SOTA-claiming papers, but making no real progress. Therefore, development of more challenging benchmarks is as important as modeling work, and publications at top-tier conferences is the least we could do to incentivize it. Also, putting data and models in different conferences is unlikely to improve the flow of ideas between the two communities.

Myth 3: A new resource must be bigger than competition

I have received a version of this myself at ACL 2020:

the new corpus presented in this work is not larger than the existing corpora.

This argument is the resource paper version of the reject-if-not-SOTA approach in reviewing NLP system papers. Test performance offers an easy heuristics to judge the potential impact of a new model, and dataset size becomes a proxy for its utility. In both cases, work from industry and well-funded labs gets an advantage.

Since large volume tends to be inversely proportional to data quality, this attitude implicitly encourages crowdsourcing and discourages expert annotation. The above ACL 2020 submission contributed a resource with expert linguistic annotation, for which there existed larger-but-noisier crowdsourced alternatives. The paper specifically discussed why directly comparing these resources by size makes little sense. Still, one of the reviewers argued that the new corpus is smaller than the crowdsourced one, and that apparently made it less valuable.

Myth 4: A resource has to be either English or very cross-lingual

The number of languages seems to perform roughly the same function as the size of the dataset: a heuristic for judging its potential impact. Here is a quote provided by Robert Munro from another ACL review:

“Overall, there is no good indication that the good results obtained … would be obtainable for other pairs of languages”

This is an absolutely valid criticism that applies… to the majority of all NLP papers, which only focus on English, but talk about modeling “language” (#BenderRule). Therefore, if this argument is allowed, every single paper must be demanded to be cross-lingual. But instead it tends to be brought up by reviewers of non-English resource papers.

The result is that such work is being marginalized and discouraged. I had a chance to visit Riga for ESSLLI 2019 and mingle with some amazing Latvian researchers who work on NLP systems for their language. They told me that they gave up on the main *ACL conferences, as their work is deemed too narrow and of no interest to the majority. This is a loss for everyone: it is far from easy to transfer ideas that worked for English to other languages, and the tricks that these Latvian researchers come up with could be of much use across the globe. Moreover, if our goal in the NLP community is to model “human language”, we are unlikely to succeed by only looking at one of them.

Conflating the number of languages with potential impact of the paper leads to an interesting consequence to cross-lingual studies: the more languages they have, the better they are in the eyes of the reviewers. However, if any meaningful analysis in all these languages is performed, the number of languages typically grows as a function of the author list length: the Universal Dependencies paper has 85 authors (Nivre et al., 2015). An average machine learning lab has no means to do anything like that, so to please the reviewers they have an incentive to resort to machine translation, even for making typological claims (Singh, McCann, Socher, & Xiong, 2019). In that case, the number of languages is unlikely to be a good proxy for the overall quality of the paper.

Myth 5: Too many datasets already

Here is an example of this argument from an EMNLP 2019 review:

This paper presents yet another question answering test.

To be fair, this particular reviewer went on to say that a new benchmark could have a place under the sun if it contributed some drastically new methodology. Still, the implicit assumption is that there should be a cap on resource papers, that it is somehow counter-productive to have a lot of question answering data.

An argument could be made that having a lot of benchmarks dilutes the community effort. However, that only holds if there is one benchmark that is inherently better than all others. If that is not the case, focusing on just one dataset is more likely to be counter-productive. With a multitude of datasets we can at least conduct better generalization studies. For instance, consider the findings that models trained on SQuAD, CoQA and QuAC do not transfer to each other, even though all three datasets are based on Wikipedia (Yatskar, 2019).

Interestingly, the same argument can be made about systems papers: should there be a cap on how many incremental modifications of BERT (Rogers, Kovaleva, & Rumshisky, 2020) the community should produce before the next breakthrough?

Myth 6: Every *ACL resource paper has to come with DL experiments

All of the above myths are straightforward to rebuff, because they reflect logical fallacies and predispositions to dislike research that does not resemble a mainstream NLP system paper. But there is one that seems to correspond to a genuine rift in the community:

Going on with the #NLProc peer review debate!

— Anna Rogers (@annargrs) April 7, 2020

The most thorny issue so far: should *ACL should require resource papers to have some proof-of-concept application?

* FOR: no ML experiments => go to LREC

* AGAINST: super-new methodology/ high-impact data could suffice

Your take?

Dozens of comments later, it became clear that people simply think of different things when they hear “resource paper”. Whether DL experiments are required or even appropriate depends on the type of contribution.

- NLP tasks/benchmarks: the main argument is typically that the new benchmark is more challenging than previous ones. That claim obviously must be supported by experimental results.

- Computational linguistic resources (lexicons, dictionaries, grammars): the value is in offering a detailed description of language from some point of view, as complete as possible. Something like VerbNet is not created for any particular DL application, and should not be required to include any such experiments.

In between these two extremes are the kinds of resources that could be easily framed as DL tasks/benchmarks, but it is not clear whether that should be required, or even is the best thing to do. Specifically, this concerns:

- Non-public data releases: the resources of data that was non publicly available before, such as anonymized medical data or data from private companies. The author contribution is the legal/administrative work that made the release possible.

- Resources with linguistic annotation (treebanks, coreference, anaphora, temporal relations, etc.): the quality of these resources is traditionally measured by inter-annotator agreement. The author contribution is the annotation effort and/or annotation methodology.

In both of these cases, the data may be used in many different ways. It could be possible to just offer standard train/test splits and present the resource as a new task or benchmark, making life easier for practitioners who are simply looking for a new task to set their favorite algorithm on. But this may be not the only, or even the best way to think of the new data. At this point, the discussion turns into an unscientific tug-of-war along the following lines:

Engineer: Is this data for me? Then I want to see experiments showing that it’s learnable.

Linguist: This is actually about language, not deep learning. But you’re welcome to use this data if you like.

In this gray area, I would make a plea for the area chairs to decide what they expect, and to make it clear to both the authors and the reviewers. Otherwise we get a review minefield situation: the baseline experiments are perceived as a hard requirement by some reviewers, but the authors did not anticipate it. Their submissions become a waste of time for the authors, the tired reviewers and the ACs. This waste could be easily prevented.

Personally, I would argue against the hard requirement of baseline experiments, for the following reasons:

- NLP is an interdisciplinary venture, and we need all the help we can get. Requiring that every submission comes wrapped in machine learning methodology would discourage the flow of data and ideas from people with different skill sets, not only in linguistics, but also fields like sociology and psychology.

- Including such experiments would likely not make either side happy. The linguists will be left with questions that could have been answered if the authors didn’t have to include baselines. The engineers would only look at the baseline section and find it unimpressive.

To give a concrete example, one of my papers contributed a new sentiment annotation scheme, a new dataset, and also showed some baseline experiments (Rogers et al., 2018). One of the weaknesses pointed out by the reviewers was this:

The results obtained using in-domain word embeddings are not surprising. It is a well-known fact that in-domain word embeddings are more informative with respect to the generic ones.

Our comment about in-domain embeddings simply described the table of results and was not meant to come as a revelation. The contribution was in the resource and methodology. But the very presence of these experiments apparently set off the wrong kind of expectations. Our paper was accepted, but many others probably fell in this trap.

How to write a good review

Am I the right reviewer for this paper?

Apples are apples, oranges are oranges, and both are good in their own way. It is pointless to reject a resource paper for not being a systems paper. To write a constructive review, first of all you need to see its contribution from the same methodological perspective as the authors. If there is a mismatch, if you’ve been assigned a paper with a type of contribution that is not in your research sphere, it is better to ask the AC to reassign it.

Here are some of the major types of resource papers, and the expertise needed to write a high-quality review:

- Crowdsourced NLP training or testing datasets: knowledge of basic crowdsourcing methodology, awareness of potential problems such as artifacts (Gururangan et al., 2018) and annotator bias (Geva, Goldberg, & Berant, 2019), as well as other available datasets for this task. Ideally, you’ve built at least one resource of this type yourself.

- Corpora with linguistic annotation (syntax, anaphora, coreference, temporal relations): knowledge of the relevant linguistic theory and annotation experience, annotation reliability estimation, and existing resources in this particular subfield. Ideally, you’ve built at least one resource of this type yourself.

- Linguistic knowledge resources (grammars, dictionaries, lexical databases): knowledge of the rest of linguistic theory and all the other relevant resources. Ideally, you’ve built at least one resource of this type yourself.

What about non-English resources? We can’t expect to always have the pool of reviewers who are experts in the right areas and also speak a given rare language, so the answer is probably “division of labor”. When we register for conferences as reviewers, we could all specify which languages we speak, in addition to our areas of expertise. If a resource (or systems) paper is not on English, the ACs would ideally try to find at least one reviewer who does speak that language, in addition to two experts in the target area. People who don’t speak the language could still evaluate the parts of the contribution that you can judge (methodology, analysis, meaningful comparisons to other work). As long as we are clear in your review what parts of the paper were out of your scope, the AC will be able to make informed decisions and recruit extra reviewers if necessary. The authors should of course help their own case by including glosses.

What makes an *ACL-worthy resource paper?

Once you made sure that you are looking at the paper from the same methodological perspective as the authors, you need to actually judge its contribution. Of course, not every resource paper deserves to be published at a top NLP conference! The acceptance criteria are really not that different for systems and resources. Most conferences are interested in how novel is the approach, how substantial the contribution, how big the potential impact. The authors of an *ACL-worthy paper, of any type, do need to make a strong case on at least one of these counts.

Here are some examples of the types of resource papers that would (and wouldn’t) fit these criteria.

-

High novelty: significant conceptual innovation

Examples: new task, new annotation methodology;

Counter-examples: using an existing framework to collect more data or update an existing resource, or simply translating an existing resource to another language. -

High impact: addressing a widespread problem, presenting new methodology with high generalizability (across languages or tasks).

Examples: discovering biases that affect multiple datasets, releasing time-sensitive data (e.g. the recent dataset of research papers on coronavirus);

Counter-examples: mitigating a specific bias induced by annotator guidelines in one specific dataset. -

High quality, richness, or size: significant public data releases that offer clear advantages in the depth of linguistic description, data quality, or volume of the resource.

Examples: linguistic databases like VerbNet, corpora with linguistic annotation, data collected organically in specific contexts (such as anonymized medical data);

Counter-examples: noisy data without clear advantages over alternatives, non-openly-available data.

To reiterate: a paper could be publication-worthy by meeting only one of these criteria. A narrow problem can be solved in a highly novel way. A noisy dataset can have high impact if it’s all there is. A resource simply recast to another language might make big waves if it shows that the techniques developed for the English version completely fail to generalize. But the authors do need to show that at least one criterion applies strongly, and convince the reviewers that there are no serious flaws (e.g. if the inter-annotator agreement was inflated by discarding large portions of data).

Note: the post was updated on 20.04.2020 and 09.05.2020.

Acknowledgements

A lot of amazing #NLProc people contributed to the Twitter discussions on which this post is based. In alphabetical order:

Emily M. Bender Follow Emily M. Bender, Ari Bornstein Follow Ari Bornstein, Sam Bowman Follow Sam Bowman, Jose Camacho-Collados Follow Jose Camacho-Collados, Chris Curtis Follow Chris Curtis, Leon Derczynski Follow Leon Derczynski, Jack Hessel Follow Jack Hessel, gdupont@localhost Follow gdupont@localhost, Yoav Goldberg Follow Yoav Goldberg, Kyle Gorman Follow Kyle Gorman, Venelin Kovatchev Follow Venelin Kovatchev, Nikhil Krishnaswamy Follow Nikhil Krishnaswamy, lazary Follow lazary, Mike Lewis Follow Mike Lewis, Tal Linzen Follow Tal Linzen, Florian Mai Follow Florian Mai, Yuval Marton Follow Yuval Marton, Emiel van Miltenburg Follow Emiel van Miltenburg, Robert (Munro) Monarch Follow Robert (Munro) Monarch, Anna Rumshisky Follow Anna Rumshisky, SapienzaNLP Follow SapienzaNLP, Nathan Schneider Follow Nathan Schneider, Marc Schulder Follow Marc Schulder, Luca Soldaini Follow Luca Soldaini, Jacopo Staiano Follow Jacopo Staiano, Piotr Szymański Follow Piotr Szymański, Markus Zopf Follow Markus Zopf, Niranjan Balasubramanian Follow Niranjan Balasubramanian

Myself: Follow Anna Rogers

References

- Bawden, R., Rosset, S., Lavergne, T., & Bilinski, E. (2019). DiaBLa: A Corpus of Bilingual Spontaneous Written Dialogues for Machine Translation.

@misc{bawden2019diabla, title = {DiaBLa: A Corpus of Bilingual Spontaneous Written Dialogues for Machine Translation}, author = {Bawden, Rachel and Rosset, Sophie and Lavergne, Thomas and Bilinski, Eric}, year = {2019}, eprint = {1905.13354}, archiveprefix = {arXiv}, primaryclass = {cs.CL} } - Geva, M., Goldberg, Y., & Berant, J. (2019). Are We Modeling the Task or the Annotator? An Investigation of Annotator Bias in Natural Language Understanding Datasets. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/D19-1107

@inproceedings{GevaGoldbergEtAl_2019_Are_We_Modeling_Task_or_Annotator_Investigation_of_Annotator_Bias_in_Natural_Language_Understanding_Datasets, title = {Are {{We Modeling}} the {{Task}} or the {{Annotator}}? {{An Investigation}} of {{Annotator Bias}} in {{Natural Language Understanding Datasets}}}, shorttitle = {Are {{We Modeling}} the {{Task}} or the {{Annotator}}?}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the 2019 {{Conference}} on {{Empirical Methods}} in {{Natural Language Processing}} and the 9th {{International Joint Conference}} on {{Natural Language Processing}} ({{EMNLP}}-{{IJCNLP}})}, author = {Geva, Mor and Goldberg, Yoav and Berant, Jonathan}, year = {2019}, pages = {1161--1166}, publisher = {{Association for Computational Linguistics}}, address = {{Hong Kong, China}}, doi = {10.18653/v1/D19-1107}, url = {https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/D19-1107} } - Gururangan, S., Swayamdipta, S., Levy, O., Schwartz, R., Bowman, S., & Smith, N. A. (2018). Annotation Artifacts in Natural Language Inference Data. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N18-2017

@inproceedings{GururanganSwayamdiptaEtAl_2018_Annotation_Artifacts_in_Natural_Language_Inference_Data, title = {Annotation {{Artifacts}} in {{Natural Language Inference Data}}}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the 2018 {{Conference}} of the {{North American Chapter}} of the {{Association}} for {{Computational Linguistics}}: {{Human Language Technologies}}, {{Volume}} 2 ({{Short Papers}})}, author = {Gururangan, Suchin and Swayamdipta, Swabha and Levy, Omer and Schwartz, Roy and Bowman, Samuel and Smith, Noah A.}, year = {2018}, pages = {107--112}, publisher = {{Association for Computational Linguistics}}, address = {{New Orleans, Louisiana}}, doi = {10.18653/v1/N18-2017}, url = {https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/N18-2017} } - Nivre, J., Agić, Ž., Aranzabe, M. J., Asahara, M., Atutxa, A., Ballesteros, M., … Zhu, H. (2015). Universal Dependencies 1.2. LINDAT/CLARIAH-CZ Digital Library at the Institute of Formal and Applied Linguistics (ÚFAL), Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University.

@article{NivreAgicEtAl_2015_Universal_Dependencies_12, title = {Universal Dependencies 1.2}, author = {Nivre, Joakim and Agić, Željko and Aranzabe, Maria Jesus and Asahara, Masayuki and Atutxa, Aitziber and Ballesteros, Miguel and Bauer, John and Bengoetxea, Kepa and Bhat, Riyaz Ahmad and Bosco, Cristina and Bowman, Sam and Celano, Giuseppe G. A. and Connor, Miriam and de Marneffe, Marie-Catherine and Diaz de Ilarraza, Arantza and Dobrovoljc, Kaja and Dozat, Timothy and Erjavec, Tomaž and Farkas, Richárd and Foster, Jennifer and Galbraith, Daniel and Ginter, Filip and Goenaga, Iakes and Gojenola, Koldo and Goldberg, Yoav and Gonzales, Berta and Guillaume, Bruno and Hajič, Jan and Haug, Dag and Ion, Radu and Irimia, Elena and Johannsen, Anders and Kanayama, Hiroshi and Kanerva, Jenna and Krek, Simon and Laippala, Veronika and Lenci, Alessandro and Ljubešić, Nikola and Lynn, Teresa and Manning, Christopher and Mărănduc, Cătălina and Mareček, David and Martínez Alonso, Héctor and Mašek, Jan and Matsumoto, Yuji and McDonald, Ryan and Missilä, Anna and Mititelu, Verginica and Miyao, Yusuke and Montemagni, Simonetta and Mori, Shunsuke and Nurmi, Hanna and Osenova, Petya and Øvrelid, Lilja and Pascual, Elena and Passarotti, Marco and Perez, Cenel-Augusto and Petrov, Slav and Piitulainen, Jussi and Plank, Barbara and Popel, Martin and Prokopidis, Prokopis and Pyysalo, Sampo and Ramasamy, Loganathan and Rosa, Rudolf and Saleh, Shadi and Schuster, Sebastian and Seeker, Wolfgang and Seraji, Mojgan and Silveira, Natalia and Simi, Maria and Simionescu, Radu and Simkó, Katalin and Simov, Kiril and Smith, Aaron and Štěpánek, Jan and Suhr, Alane and Szántó, Zsolt and Tanaka, Takaaki and Tsarfaty, Reut and Uematsu, Sumire and Uria, Larraitz and Varga, Viktor and Vincze, Veronika and Žabokrtský, Zdeněk and Zeman, Daniel and Zhu, Hanzhi}, year = {2015}, url = {http://hdl.handle.net/11234/1-1548}, journal = {LINDAT/CLARIAH-CZ digital library at the Institute of Formal and Applied Linguistics (ÚFAL), Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University} } - Rogers, A., Kovaleva, O., & Rumshisky, A. (2020). A Primer in BERTology: What We Know about How BERT Works. ArXiv:2002.12327 [Cs].

@article{RogersKovalevaEtAl_2020_Primer_in_BERTology_What_we_know_about_how_BERT_works, title = {A {{Primer}} in {{BERTology}}: {{What}} We Know about How {{BERT}} Works}, shorttitle = {A {{Primer}} in {{BERTology}}}, author = {Rogers, Anna and Kovaleva, Olga and Rumshisky, Anna}, year = {2020}, url = {http://arxiv.org/abs/2002.12327}, archiveprefix = {arXiv}, journal = {arXiv:2002.12327 [cs]}, primaryclass = {cs} } - Rogers, A., Romanov, A., Rumshisky, A., Volkova, S., Gronas, M., & Gribov, A. (2018). RuSentiment: An Enriched Sentiment Analysis Dataset for Social Media in Russian. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 755–763. Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics.

@inproceedings{RogersRomanovEtAl_2018_RuSentiment_Enriched_Sentiment_Analysis_Dataset_for_Social_Media_in_Russian, ids = {RogersRomanovEtAl\_2018\_RuSentiment\_An\_Enriched\_Sentiment\_Analysis\_Dataset\_for\_Social\_Media\_in\_Russian}, title = {{{RuSentiment}}: {{An Enriched Sentiment Analysis Dataset}} for {{Social Media}} in {{Russian}}}, shorttitle = {{{RuSentiment}}}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the 27th {{International Conference}} on {{Computational Linguistics}}}, author = {Rogers, Anna and Romanov, Alexey and Rumshisky, Anna and Volkova, Svitlana and Gronas, Mikhail and Gribov, Alex}, year = {2018}, pages = {755--763}, publisher = {{Association for Computational Linguistics}}, address = {{Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA}}, url = {http://aclweb.org/anthology/C18-1064} } - Singh, J., McCann, B., Socher, R., & Xiong, C. (2019). BERT Is Not an Interlingua and the Bias of Tokenization. Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Deep Learning Approaches for Low-Resource NLP (DeepLo 2019), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/D19-6106

@inproceedings{SinghMcCannEtAl_2019_BERT_is_Not_Interlingua_and_Bias_of_Tokenization, title = {{{BERT}} Is {{Not}} an {{Interlingua}} and the {{Bias}} of {{Tokenization}}}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the 2nd {{Workshop}} on {{Deep Learning Approaches}} for {{Low}}-{{Resource NLP}} ({{DeepLo}} 2019)}, author = {Singh, Jasdeep and McCann, Bryan and Socher, Richard and Xiong, Caiming}, year = {2019}, pages = {47--55}, publisher = {{Association for Computational Linguistics}}, address = {{Hong Kong, China}}, doi = {10.18653/v1/D19-6106}, url = {https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/D19-6106} } - Yatskar, M. (2019). A Qualitative Comparison of CoQA, SQuAD 2.0 and QuAC. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 2318–2323.

@inproceedings{Yatskar_2019_Qualitative_Comparison_of_CoQA_SQuAD_20_and_QuAC, title = {A {{Qualitative Comparison}} of {{CoQA}}, {{SQuAD}} 2.0 and {{QuAC}}}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the 2019 {{Conference}} of the {{North American Chapter}} of the {{Association}} for {{Computational Linguistics}}: {{Human Language Technologies}}, {{Volume}} 1 ({{Long}} and {{Short Papers}})}, author = {Yatskar, Mark}, year = {2019}, pages = {2318--2323}, url = {https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/papers/N/N19/N19-1241/} }

Share / cite / discuss this post

Special thanks go to EMNLP 2020 organizers.